The Maya definitely knew how to party, but they didn’t get their kicks by just dancing and singing during the sacrificial ceremonies; they had lots of pharmaceuticals they employed to help them get “elevated.”

Psilocybin mushrooms

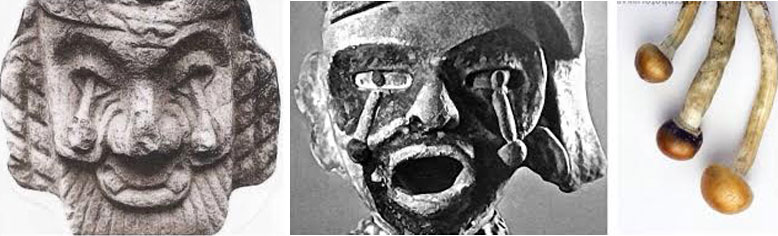

The entheogenic mushroom genus Psilocybe includes at least 54 species that are found in Mexico. The Maya used one of them (called K’aizalaj Okox in Mayan) in their ceremonies for its hallucinogenic properties. They illustrated this use in many of their anthropomorphic idols, especially the ones commonly associated with the god Quetzalcoatl in his incarnation as Ehecatl, the god of wind, by portraying the hallucinations as mushrooms dangling from the god’s eye sockets.

The entheogenic mushroom genus Psilocybe includes at least 54 species that are found in Mexico. The Maya used one of them (called K’aizalaj Okox in Mayan) in their ceremonies for its hallucinogenic properties. They illustrated this use in many of their anthropomorphic idols, especially the ones commonly associated with the god Quetzalcoatl in his incarnation as Ehecatl, the god of wind, by portraying the hallucinations as mushrooms dangling from the god’s eye sockets.

A couple examples are below:

Xtabentun seeds and nectar

The seeds of morning glory Turbina corymbosa (xtabentun in Mayan) were used by the Maya for their psychotropic effects. The seeds of the plant contain the ergot alkaloids ergine, isoergine, chanoclavine, elymoclavine, and lysergol, which act on the brain in a manner similar to LSD.

Ethnohistorical accounts of use of these plants date to the 16th century, when Francisco Hernández described how the seeds were employed. He reported that a fully hallucinogenic dose contained 100-150 ground seeds dissolved in cold water.

In 1591, Juan de Cárdenas described how the altered mental state these seeds produced were perceived by shamans as conducive to soothsaying: “when taken by mouth, will cause the wretch who takes them to lose his wits so severely that he sees the devil among other terrible and fearsome apparitions; and he will be warned (so they say) of things to come, and all this must be tricks and lies of Satanas, whose nature is to deceive, with divine permission, the wretch who on such occasions seeks him”.

The hallucinogenic properties of the xtabentun plant can also be passed through the nectar of its flowers to bee honey. When this hallucinogenic honey is fermented into an alcoholic drink, it carries a double whammy.

Another morning glory plant, Ipomea violacea (Xha’il in Mayan) contains the same alkaloids as xtabentun and was used by the Maya in the same manner to get stoned.

Bufotoxins

Bufotoxins, found in the parotid glands of different toad species, are toxic substances with psychoactive properties. In Mexico, toads of the Bufo genus secrete this milky, toxic stuff (bufotenin) to dissuade predators. Animals that ingest the venom, or eat the toad, may experience cardiovascular and gastrointestinal symptoms.

Secretions from the Bufo marinus also have been used to induce trance states since Olmec times. Large quantities of the remains of these toads have been found in San Gervasio’s ruins as well as in other Maya sites on the island during the 1972-3 excavations by Harvard and Arizona Universities.

Historians of the 16th century stated that the Maya added the skins of the Bufo marinus to their alcoholic drinks to increase their potency. The K’iche’ Maya still use the skin of this amphibian as an ingredient in their balché. The Maya made the drink by infusing the bark of the Lonchocarpus longistylus tree in mead made from honey produced by stingless bees that fed on the nectar of xtabentun flowers.

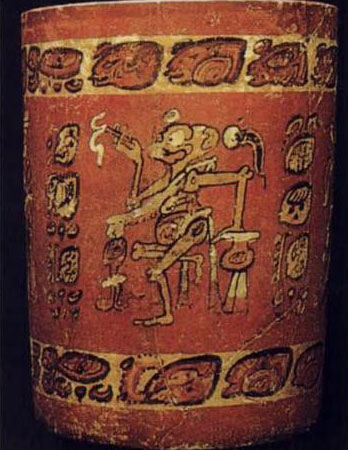

Above: A Maya drinking vessel for toad-juice infused balché from the Classic period.

Ethnobotanist Jonathan Ott published the results of a study in which he self-administered free base bufotenin. Ott reported “visionary effects” and that the “visionary threshold dose” was 40 mg, with smaller doses eliciting perceptibly psychoactive effects. He reported the experience “is throughout quite physically relaxing; in no case was there facial rubescence, or any discomfort nor disesteeming side effects.” Ott stated the effects began within 5 minutes, peaked at 35–40 minutes, and lasted up to 90 minutes. Higher doses produced effects that were described as psychedelic, such as “swirling, colored patterns typical of tryptamines, tending toward the arabesque.”

Alcohol

The Maya fermented various types of plants to make alcoholic drinks. The above-mentioned mead called balché was one of them. Chi was another (also called pulque), made from the sap of the maguey. Pineapples, corn, guanabana (soursop), and other fruit containing high levels of sugar were also fermented into alcoholic beverages by the Maya.

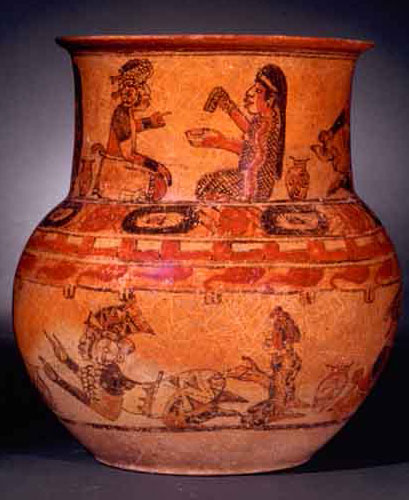

Above: A fresco showing Maya drinking balché…

…and what’s a Maya drinking party without someone puking?

The Maya not only drank these types of alcohol, but they also employed alcoholic enemas in order to get thoroughly inebriated. The enema tool was a long-necked gourd with a hole cut in the tip of the neck as well as a larger hole on the side which was used to fill it with the liquid. Occasionally, a ceramic version of this tool was used, examples below:

Above: A Maya figurine of a happy drunk self-administering an alcohol enema.

Above: More figurines showing alcohol self-administered enemas.

Above: Another Maya self-administering an enema in order to get rip-roaring drunk.

Above: A Maya on the receiving end of an alcohol enema.

Above: One more…

Xtabentun

The Maya fermented things to make alcohol, but never discovered the art of distillation prior to the arrival of the Spanish. Today’s liqueur called xtabentun is not a traditional Maya drink, but rather an invention of the Spanish, who disliked the flavor of balché. The Spanish distilled mead (fermented honey) into liquor and then added anise to the drink to get its distinctive licorice flavor. The standardized, commercial production of xtabentun didn’t begin until the 1930s.

Tobacco

Pre-conquest Maya used Nicotiana rustica (wild tobacco, or kutz, in Mayan) in various ways in order to achieve a different level of consciousness. The species of tobacco in the commercially produced cigarettes and cigars we have today only contain around 3% of the alkaloid nicotine. Nicotiana rustica can contain up to 18% of this active ingredient. At that level of efficacy, nicotine is hallucinogenic.

Mai, a powdered form of wild tobacco mixed with lime, was used by the Yucatec Maya’s lower classes on a daily basis. They kept this mixture tied to their waist in a long-necked gourd (called a bux) and used a long-handled scoop made of deer-bone or wood to fish out the ground tobacco and lime mixture. A walnut-sized wad of this stuff was inserted between the cheek and gum, which they said helped alleviate hunger and thirst.

The Maya elite used ceramic containers for their tobacco. Below is a small, 1,300-year-old Maya powdered-tobacco container that was found to still contain traces of Nicotiana rustica. The 1,300-year-old flask was made in what is now Mexico’s southern Campeche state. The phrase “y-otoot ‘u-may,” written on the vessel in glyphs, translates as “the house of his/her tobacco.”

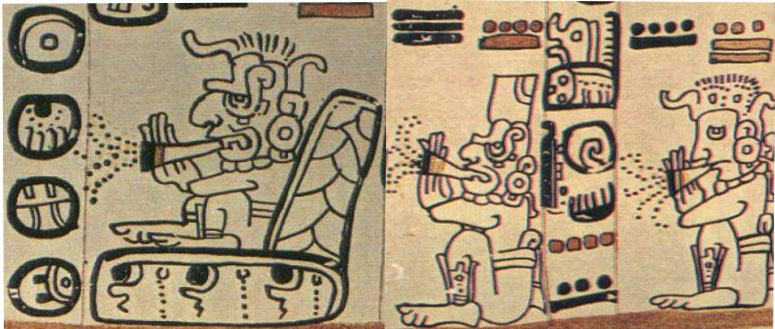

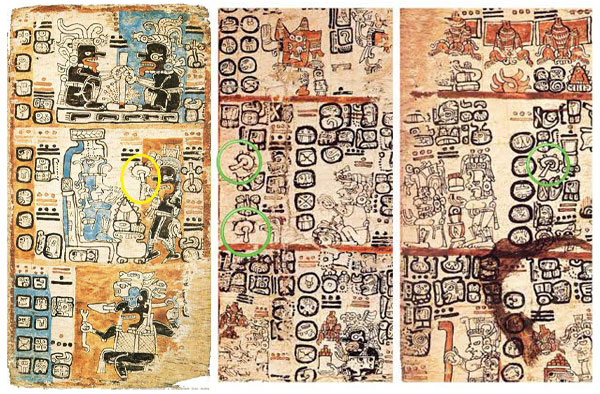

The Maya also smoked Nicotiana rustica in the form of cigars, or sikar, in Mayan, in order to experience the hallucinogenic properties of this powerful species of tobacco. The Spanish were offered these wild-tobacco cigars and smoked them with the Maya in 1518 when Juan de Grijalva “discovered” Cozumel. These sikars were not always rolled in tobacco-leaf wrappers like we make cigars today, but were often made by stuffing lengths of reeds with tobacco and smoking the lit reed. Below are two images of Maya smokers from the Madrid Codex, a pre-Hispanic document drawn by Maya priests:

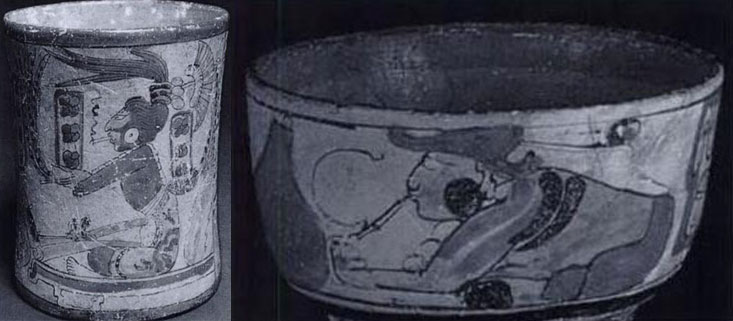

Below are two classic period ceramics showing the act of smoking.

The left piece is from Yucatan. The right one is from Guatemala.

Below is a Late Classic period jar showing an image of the god of death, dancing and smoking:

Marijuana

Believe it or not, the Maya did not smoke pot. That is because marijuana (Cannabis sativa or Cannabis indica) was not found in Mexico (or the New World, for that matter) until after the Spanish arrived and brought it with them from the Old World.

Another plant the pre-Colombian Maya never used was the coconut. The Spanish brought the first coconuts to Mexico from the Philipines in the 1600s. The coconut palm tree did not reach Quintana Roo until the 1700s.

More magic mushrooms

Amanita muscaria is commonly known as the fly agaric or fly amanita. It is a psychoactive fungus. The main psychotropic ingredient is Muscimol (also known as agarin or pantherine) which produces sedative-hypnotic effects on the brain as well as dissociative psychoactivity. The Maya used it in many of their ceremonies and it is depicted in many of their ceramics, codices, and bas-reliefs.

Above, on the left, is a bearded dwarf, holding a shield and wearing a hat designed as an upside down Amanita mushroom (Princeton Art Museum). In Mesoamerican mythology the dwarf is related to Quetzalcoatl and guides the dead in their descent into the underworld.

Above: A portion of the Madrid Codex showing Amanita mushrooms, circled.

Water Lily

Parts of the Water Lily (Nymphaea ampla, or Na’ab, in Mayan) were also used by the Maya and acted much like morphine. The image of the plants appears frequently in vessels illustrated with scenes depicting rituals involving divinations.

Other hallucinogenic plants used by the Maya:

• The seeds of Erythina coralloides (xk’olok’max in Mayan) were mentioned in the Popol Vuh

• Wormwood (Artemisia mexicana, or tsi’tsim in Mayan); wormwood is the plant with the psychoactive ingredient originally used in absinth

• Tagetes lucida, (xpuhuk in Mayan) was powdered and blown into he faces of some sacrificial victims to “dull their senses” prior to being dispatched

• Datura stramonium (tohk’u in Mayan), a plant in the nightshade family which is also known as Jimson weed and Locoweed

• Datura candida also known as the Devil’s Trumpet or “Vuelveteloco,” contains both hiosciamine and scopolamine. This plant was used in the bloodletting rituals, to kill the pain, and in better communication with the gods.

Copyright 2017, Ric Hajovsky