The performance presented by the Papantla Flyers (the Voladores) at Discover Mexico Park is a reenactment of part of a ritual that has been taking place in Mexico, uninterrupted, for over 2,500 years. The ceremony began in the central part of Mexico with the Olmecs. Over time, it was incorporated into the central Mexican cultures that followed: the Totonacos, Huastecas, Nauhuas, Otomis, Chichimecas, Cuicatecos, Tepehuas, Toltecs, Mexicas, and Aztecas. The ceremony was also performed by the Huicholes and Coras in northern Mexico and by the Hopi in Arizona. The Quiche Maya in Guatemala, the Nicarao people of Nicaragua, and the Pipiles of El Salvador performed the ceremony on a regular basis as well.

The performance presented by the Papantla Flyers (the Voladores) at Discover Mexico Park is a reenactment of part of a ritual that has been taking place in Mexico, uninterrupted, for over 2,500 years. The ceremony began in the central part of Mexico with the Olmecs. Over time, it was incorporated into the central Mexican cultures that followed: the Totonacos, Huastecas, Nauhuas, Otomis, Chichimecas, Cuicatecos, Tepehuas, Toltecs, Mexicas, and Aztecas. The ceremony was also performed by the Huicholes and Coras in northern Mexico and by the Hopi in Arizona. The Quiche Maya in Guatemala, the Nicarao people of Nicaragua, and the Pipiles of El Salvador performed the ceremony on a regular basis as well.

Originally, the ritual was part of the observance of the end of a 52-year cycle the Olmecs defined as the synchronization of their 260-day ritual calendar and their 365-day solar calendar. Many aspects of the dance, such as the number of participants, the number of steps they made as they danced around the pole, and the number of rotations made as they descended related to this observance of the calendar round. Later, as the rite spread though geographical area and time periods, each culture altered it a little, adding bits of their own to the performance, deleting others, and often dedicating it to a different god.

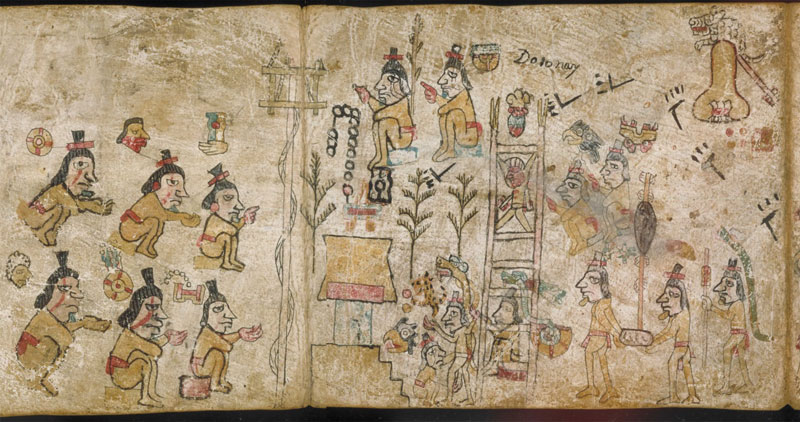

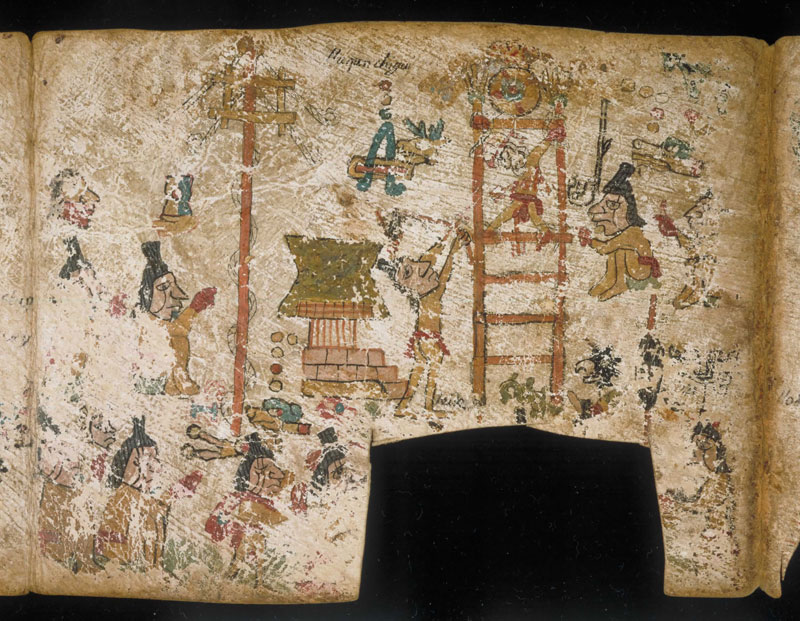

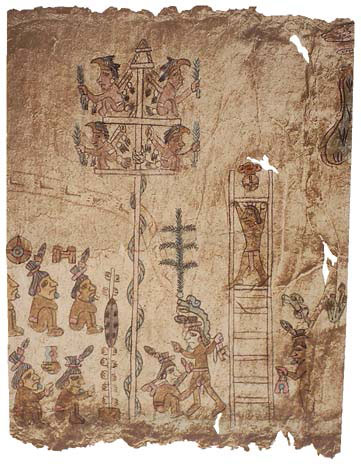

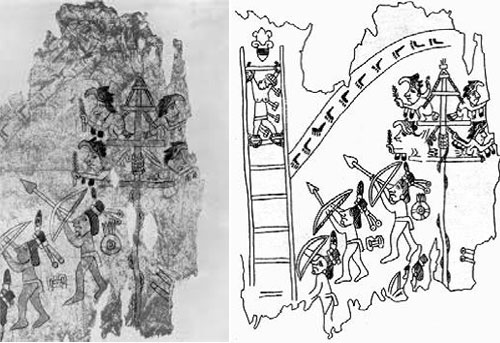

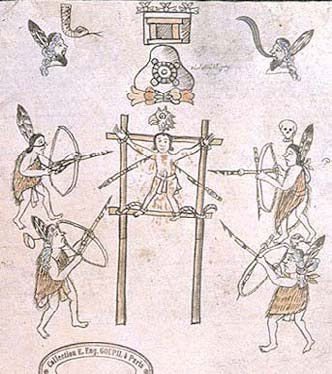

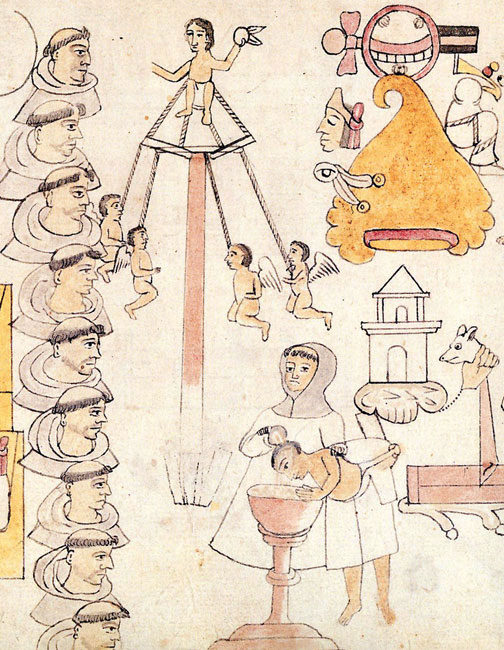

One of the most common reasons these cultures observed the ceremony was to insure a bountiful harvest. To that end, a human sacrifice was added to the ceremony, one which has been well-documented in both the indigenous, hand-painted picture books known as codices as well as the writings of early Spanish observers. The sacrificial victim, sometimes a woman or young girl, but frequently a man, was tied upright, spread-eagle on a ladder-type scaffold (cadalso). When the spiraling Voladores dancers reached the ground, a priest pierced the victim’s groin with an arrow shot from a bow. Quickly thereafter, other participants shot more arrows into the victim’s body, eventually resulting death. The body was allowed to hang so that the blood drained onto the ground, which these early cultures believed would replenish the earth’s fecundity.

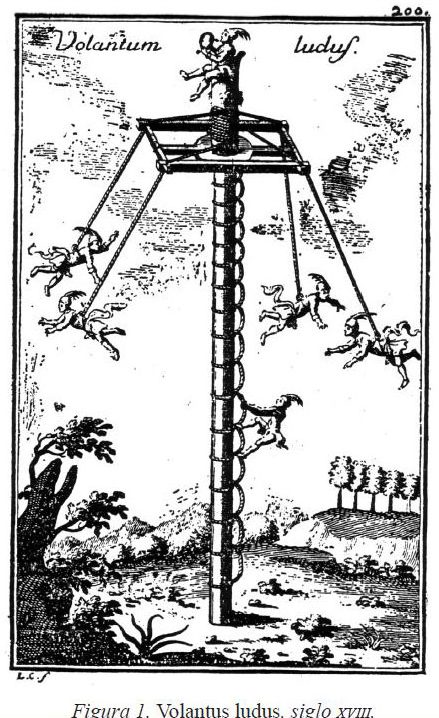

After the Spanish conquest, the Spanish priests did their best to stamp out all indigenous “pagan” beliefs, and the Voladores ritual, as well as the Arrow Sacrifice, were outlawed. However, this situation did not last long. The Indians were willing to give up human sacrifice, but not the exciting event of the Voladores performance. Spanish historian and priest, Juan de Torquemada wrote in his 1612 book, Los veinte y un libros rituales y monarchia Indiana, that the Voladores dance was soon being performed without the accompanying human sacrifice or with the ritual connections to the 52-year calendar round: “The flight did not cease with the Conquest nor with the introduction of the Faith to the Indians but continued until the clergy discovered its secret meaning and then it was strictly prohibited. However, once the first of the idolaters who had received the Faith were dead and the sons who followed them had forgotten the idolatry the flight represented, the flights resumed. The flights were performed on many occasions, and, like those who take advantage only of the sport and not the intent which their fathers had… no one cares that the turns be only thirteen [anymore].”

As time went by, the Voladores ceremony continued to evolve and in some places it was abandoned entirely. One of the locales where the rite is still practiced frequently is in the area of Papantla, Veracruz, Mexico. In 1975, a group of Papantla Voladores organized themselves into a union, la Unión de Danzantes y Voladores de Papantla. Later, other workers’ unions sprang up: Asociación de Voladores independiente de Papantla Kgosni, S.C., Asociación de Voladores Tutunakú, Asociación de Voladores Libres de la Costa, and Asociación de Voladores Libres de la Sierra. These unions all attempt to standardize the abbreviated ritual performed today, and also prevent non-union members from performing it for pay. However, in several other places, like the Quiche Maya villages in Guatemala, it is still performed without a union structure.

In September, 2009, UNESCO named the ritual an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Copyright 2015, Ric Hajovsky