Over 35 years ago, when I wrote my first travel guide to Cozumel, I included the recommendation that before you go to the east coast of the island, first go by a tlapalería and buy a small bottle of tiner (paint thinner) so you could clean the tar off of your feet after walking on the beach. Back then, we had very little trash on the east coast beaches, but loads of tar and crude oil residue. Today, the tar has disappeared, along with most tlapalerías. However, the amount of garbage one finds today on the east coast beaches of Cozumel is truly astounding.

Where does it all come from? If you ask people living on Cozumel where all the debris comes from, most of them say “it comes from the Cruise Ships.” If you ask tourists the same question, they say “it’s left by the Mexicans.” I suspected neither of these two statements was true, so I made a little experiment.

I went to a stretch of sandy beach on the east side of the island and marked off a 300-meter-long length of beachfront. Then, I walked along this stretch while examining the garbage that was there, and picked up any examples that had a label on it that stated the country of manufacture. Obviously, there were many, many pieces whose paper labels had washed off, or whose inked labels had faded away, but there were still plenty of pieces of refuse with legible labels. I found several items listing the country of manufacture as USA, China, or Canada. This does not mean, however, that these particular pieces of litter were tossed or washed into the sea directly from these three countries. These products were most likely first exported to countries bordering the Caribbean and then their containers were thrown away in the country that imported them. Since I had no way of finding out where they were discarded, I did not count them in my experiment.

The two countries of origin that I encountered most frequently were Haiti and Dominican Republic, both of which occupy the Caribbean island of Hispaniola. The Haitian product packages were mostly beauty products (35), Barbancourt and Bakara Rum bottles (6), skin lightener (8) plastic butter tubs (13) and assorted other bottles and bottle caps (16). I suspect that many of the disposable razors (50+) whose blades had been removed (for recycling?) also came from Haiti, but I couldn’t be sure. By the looks of the large amount of completely worn-out toothbrushes (41) and toothpaste tubes that had been squeezed bone-dry (18), or cut in half to get the last drop of toothpaste out (7 halves), I would imagine these also came from a very poor nation like Haiti; but again, that’s just a guess. The products from the Dominican Republic were mostly beauty aids, bottles, and medicine containers. The next countries represented in the sampling, in order of precedence, were Jamaica, Venezuela, Honduras, Cuba, Guatemala, Colombia, Mexico, Nicaragua, Curaҫao, St. Vincent & the Grenadines and Trinidad. Note how far down the list Mexico ranked as a polluter-nation.

I found three pieces, oddly enough, manufactured in El Salvador, a small Central American country on the Pacific coast. They had probably been imported into Guatemala or Honduras and then discarded from one of those countries. The one solitary item (a tube of anti-wrinkle cream) labeled “Made in Chile” and the single medicine bottle labeled in Arabic I have no way of reckoning how they made it to Cozumel.

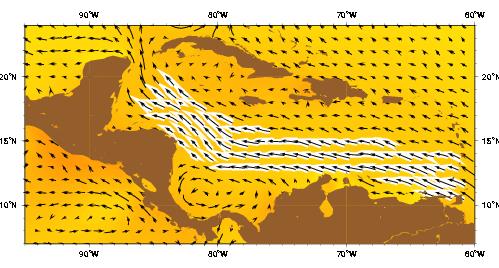

I found no Costa Rican or Panamanian items, but looking at the circular motion of the gyre current that peels off from the main northward-flowing Caribbean current, I am not surprised. Trash originating from these two Central American countries is most likely doomed to end up as part of some huge raft of floating debris stuck in the middle of this gyre. See the chart below to see the direction of the Caribbean ocean currents.

The following are the categories of items that had no indication of country of origin, listed from the most frequently occurring to the least frequently occurring, but with at least 10 individual examples found in each category:

bottle caps (outnumbering everything else 1,000s to 1)

beauty products

small chlorine bottles (for purifying water)

food and beverage containers

toothbrushes

disposable razors

disposable butane lighters

healthcare products (including syringes, douches, and enema bottles)

brushes and combs

hair curlers and hair clips

shoes and sandals

pens and markers

plastic clothespins and clothes hangers

toys

small plastic vinegar bottles

liquor bottles

Another category that was fairly well represented was what I called “Things lost or jettisoned from a small fishing boat.” This category included, in descending order of occurrence:

plastic motor oil bottles

empty water bottles

plastic bottles tied with cord and used as buoys

plastic jugs cut to serve as bailers

oars, paddles, and bait-cutting boards

ruptured gas cans

buoys

fragments of fishing nets

fishing line

Another category was made up of items that I suspect were left on the Cozumel beach by either tourists or locals. The items in this category included (in descending order of occurrence):

plastic knives, forks, and spoons

disposable plastic plates

Mexican beer bottles

disposable diapers

As far as items that could be traced back to Cruise-ships, I found no “smoking guns.” However, I did find a number of items from France, Greece, Italy, and the Netherlands, along with one unused condom made in Germany that was still in its original package. These items seemed to me to be more indicative of things purchased by the crew of cargo ships or tanker ships. Other items that looked to be items lost or jettisoned by cargo ships included hard-hats, plastic hoses, and an orange safety vest.

In conclusion, I believe that over 90% of the litter that festoons the east coast of Cozumel originates as garbage deliberately dumped into rivers, bays, or ocean by residents of the countries located in the north coast of South America, the greater and Lesser Antilles, or Central America north of Costa Rica.

Below are a few of the many, many labels I encountered during my search through the beach debris:

copyright 2014, Ric Hajovsky