Mistakes, Misstatements, and Misunderstandings;

The Mythologies Surrounding San Miguel

There have been many garbled and fictitious stories published about the statue of the Archangel Michael in the church at Juarez and 5 Avenue in downtown San Miguel, Cozumel over the years. Most of the stories have at least a few of the following points in common:

1. The statue is believed to be about 500 years old.

2. It was found by workers digging in a field north of town (sometimes it is construction workers) over 100 years ago.

3. It was originally brought to Cozumel by Juan de Grijalva in 1518.

4. Since the find came on Sept. 29, the saint’s feast day, they decided to name Cozumel’s main urban area in honor of the saint.

5. Juan de Grijalva introduced Christianity to the island and placed the statue in a Catholic Temple that was located in the town’s central plaza.

6. The statue was later sent to Merida for restoration, but the restorers kept the original and sent a new one in its place.

In fact, although they have been printed and reprinted in many guides, books, and web pages over the years, not a single one of these statements is true. If you really want to know about the statue and the early history of Cozumel, here are the facts:

Juan de Grijalva was sent to the Yucatan from Santiago, Cuba by the governor to explore the mainland of Mexico as a follow up of Francisco Hernández de Cordoba’s expedition of 1517. Grijalva first landed on the north-eastern shore of Cozumel Island on May 3, 1518, the day the Spanish celebrate as the day of the Holy Cross, so he named the island Santa Cruz.

Grijalva’s ships then rounded the southern tip of the island and landed on the south-western shore, where they found Maya buildings and named the place “San Felipe y Santiago.” Saint Philip and Saint James were two apostles whose holy days are celebrated together, on May 3 as well. Later, on May 6, they reached the Maya village of Xamancab (the site of today’s San Miguel de Cozumel) and named it San Juan Ante Portam Latinam, or “Saint John before the Latin Gate,” after the Apostle Saint John, whose holy day it was. The Portam Latinam portion of the name is a reference to a gateway in Rome where the apostle was thrown into a pot of boiling oil.

Grijalva then had a mass said on the steps of one of temples at the Maya village. The Spaniards’ stay in Cozumel is well documented in reports written by two of the expedition members. One of the reports was entitled Itinerario de la armada del rey católico a la isla de Yucatán, en la India, en el año 1518, en la que fue por comandante y capitán general Juan de Grijalva, escrito para Su Alteza por el capellán mayor de la dicha armada, and was written by Juan Díaz Núñez, the expedition’s chaplain. This report said absolutely nothing about a statue being given to the Maya of Cozumel, something one would assume would be of great interest to a chaplain.

A later expedition to Cozumel led by Hernán Cortés was also well documented by two of his expedition members, and it was recorded in both accounts that Cortés left an image of the Virgin Mary with the Maya when he left. It seems likely that this account of Cortés leaving a religious icon on the island somehow became confused and superimposed over Grijalva’s visit by folks later retelling the story.

The downtown area of San Miguel was later briefly occupied as the Spanish military garrison of Arenal, established by Pánfilo de Narváez in April of 1520. On September 29, 1527, Francisco Montejo the Elder landed on Cozumel and gave the village there the name San Miguel de Xamancab, after the Mayan name of the place, Xamancab, meaning “Northland,” and for the saint whose day was celebrated on September 29, the Archangel Saint Michael (Archangel San Miguel). This is the first time the name San Miguel is associated with the village.

In the mid-1550s, a Catholic church was erected in the town, but the island was left to more-or-less fend for itself as the Spaniards concentrated their efforts on other, more lucrative parts of the mainland. During the late-1500s, this settlement of semi-Christianized Maya on Cozumel was the target of several pirate attacks, most notably one by the French corsaire Pierre Chultot, who took up residence in the church in 1571 and used the church’s altar as his bed. After terrorizing the Maya townsfolk for almost three weeks, Pierre was captured by Spanish troops, and turned over to the people of Cozumel, who promptly hung him.

The church on Cozumel at this time was still a visita, meaning the island had no resident priest. Occasionally, a visiting padre, called a vicaria, would come from the mainland to say mass, preside over weddings, preform baptisms, and other ecclesiastical tasks. This channel-crossing was not something the vicarias looked forward to with any sort of pleasure. There exist several reports sent to the priests’ bishops complaining of the dangers the channel crossing presented. In one such report, written by Padre Baltazar de Herrera and dated 1586, the priest stated his predecessor, Padre Cristobal de Asencio, was drowned by his Maya assistants as they rowed him to the island. Another report, written in 1627 by Padre Nicolas de Tapia, states “the natives on the island and the coast are so fierce that they have drowned and killed several of their ministers and this is a risk that I undertook many times as I crossed over to the island.”

During this period, the Maya towns and ports along the coast all fell under the power of the Spanish and there was no more need for Spanish ships to make landfall first at peaceful Cozumel to re-provision after sailing in from Spain or the Caribbean. Now, they could stop anywhere along the coast first just as easily. Cozumel became a colonial backwater. With the absence of the Spanish government’s soldiers, pirates began preying on the island and the population dwindled under the constant attacks.

In 1650, many of the islanders were moved to the mainland town of Xcan Boloná to avoid the buccaneers’ attacks. Later, in 1688, more of the island’s population, as well as many of the settlements along the Quintana Roo coast, were evacuated inland to towns like Chemax.

In 1713, four ships of English buccaneers burned to the ground the last remaining buildings on Cozumel. What few survivors remained were mostly Belizeans who occupied woodcutters’ camps, where they cut logwood (palo de tinte) for shipment to England and America. A hundred years later, sometime around 1830, a cotton plantation was established at San Miguel.

In 1841, George Fisher, a Hungarian-born citizen of the five-year-old Republic of Texas, convinced the cash-strapped Yucatecan government in Merida to sell him 18 miles of Cozumel’s coastline. Fisher had it surveyed and then had crosses set up along the boundary of the property. It was his intent, along with several partners from Texas, to develop the island agriculturally and to sell land there to European immigrants. However, before the partnership’s bank in New Orleans could send the money to close the deal, the bank failed, and the project fell apart.

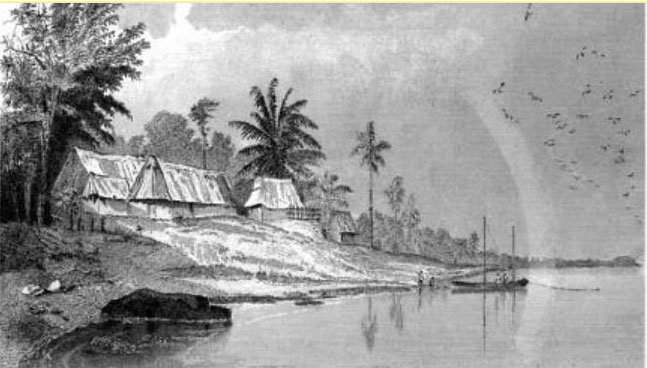

In 1841, John Lloyd Stevens and Frederic Catherwood visited Merida during their search for Mayan ruins and ran into George Fisher there. The Serbian-Texian showed the two around town and helped them make contacts for their trip to the Quintana Roo coast. Later that year, when the Stevens and Catherwood visited Cozumel (and sketched this drawing of the buildings of the San Miguel ranch for the book Incidents of Travel in the Yucatan, volume II), Don Vicente had just returned to the old rancho to retrieve some of his goods that he had left there when he fled from his irate workers. At that time, he was still calling the place San Miguel. The two adventures also described the ruins of the old Spanish church they found behind the rancho San Miguel: “…the ruins of a Spanish church, sixty or seventy feet front and two hundred deep. The front wall has almost wholly fallen, but the side walls are standing to the height of about twenty feet. The plastering remains, and along the base is a line of painted ornaments. The interior is encumbered with the ruins of the fallen roof, overgrown with bushes; a tree is growing out of the great altar, and the whole is a scene of irrecoverable destruction.” This is surely the church Pierre Chultot defiled in 1571.

In 1846, Yucatan declared itself independent from Mexico. The same year the United States and Mexico declared war with one another. In 1847, the Maya revolted against their white and mestizo oppressors and the conflict known as the War of the Castes began in Yucatan. As the war in the Yucatan progressed, and the Maya gained the upper-hand, the Yucatan Government’s treasury began to be depleted. In an attempt to raise funds, on April 18, 1848, the Governor of Yucatan, Miguel Barbachano, offered to sell the entire island of Cozumel to Spain. Spain turned down the offer.

At the same time Barbachano was trying to sell the island, the townsfolk of Valladolid began fleeing the city, just minutes ahead of the invading Maya. One group of refugees, numbering about 600, began making their way towards Rio Lagartos, under the protection of a small company of Yucatecan soldiers led by Captain Sebastian Molas, a nephew of the contrabandista Miguel Molas, who the northern tip of Cozumel, Punta Molas, was named after. The Maya were hot on the refugees trail, however, and the column was cornered against the beach near Dzilam. Just as it looked like they would be massacred by the Maya, a group of sailing vessels appeared and offered the group salvation. 121 of the evacuees boarded the American schooner Falcon and others boarded a Spanish boat and were whisked away to Havana. The rest of the refugees were picked up off the beach by the English ship True Blue captained by James Smith and taken to Cozumel.

That same year, a prelate from Chemax, Padre Doroteo Rejón (along with a medical doctor named José Antonio García), gathered up a large group of families wishing to leave the war-torn town and led them to Cozumel as well. It was with this group of refugees from Chemax, that the statue of Saint Michael the Archangel now resting on the altar of the San Miguel Catholic Church first came to the island.

The group of refugees from Chemax settled in the old rancho of San Miguel. Another group, made up mainly of Maya farmers who wanted no part of the war, took up residence in the old Maya town of Oycib, re-naming it Cedral. On November 21, 1849, the government of Yucatan officially recognized the town founded by the group of refugees who had settled on Molas’ old rancho as the “Pueblo de San Miguel de Cozumel” and linked it to the municipal government of Tizamín. San Miguel was also granted a four-year moratorium on any taxes and the adult men living there were granted an exemption from military conscription by the Yucatecan government in order to assist the fledgling settlement. In 1850, a census showed the island’s population had grown to 341 adults and an unspecified number of children. Only 6 of the adults were over the age of 50. It was also noted that in this year, the town had two streets and a square.

In February of 1877, Alice and Augustus Le Plongeon visited Cozumel during their tour of Mayan sites in the Yucatan. At this time, Padre Rejón was still the town’s priest. The Le Plongeon’s described the town as “a scattered village of 500 souls.” As there was no hotel or guest house on the island, they were offered “a dirty thatch-roofed room at the southeast corner of the immense grassy square that was the town plaza.” Padre Rejón took the two under his wing and showed them around the island, including many of the ruins and cenotes. The priest also let them in on a secret: he had the “evil-eye.” It was the belief of his congregation (and his, too) that he had the ability of fixing his gaze on something, or someone, and cause them harm. He also informed them that the house they occupied was haunted.

The Catholic church that now stands on the corner of Calle 10 and Avenida Juarez was not the one used by Padre Rejón, but a new one built by the Maryknoll Missionaries during the years 1945 and 1946. The statue of Saint Michael the Archangel that is in the church today is the same one that came to Cozumel with Padre Doroteo Rejón in 1848. It was placed in the church when the first mass was said in the new building by the Maryknoll missionary, Jorge Hogan, on May 26, 1946.

copyright 2011 by Ric Hajovsky